Children are always episodes in someone else’s narrative, not their own people, but brought forth into being for particular purposes.

So wrote historian Carolyn Steedman in her 1986 memoir Landscape for a Good Woman: A Story of Two Lives,which contrasts two working class childhoods – her mother’s in 1920s Burnley, and her own in 1950s South London – in a work that is a mélange of autobiography, social history, and psychoanalysis. “Each child grows up in an adult world that is specified by both politics and social existence,” she writes later, “and they are reared by adults who consciously know and who unconsciously manipulate the particularities of the world that shaped them.” She goes on to provide examples from her own life: her mother’s father was killed in the First World War, and her own father was “knowingly and unknowingly” removed from her.

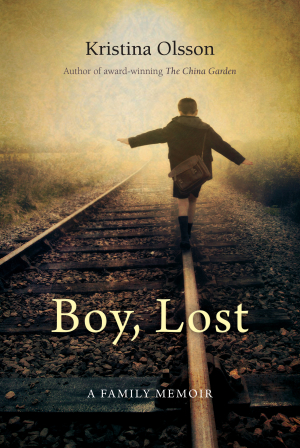

Steedman’s statement has become something of an epigraph for my own family memoir work-in-progress, What We Inherit, and it came to mind while reading Kristina Olsson’s award-winning 2013 family memoir, Boy, Lost. Peter, the eponymous ‘lost boy’ was just sixteen months old when he was separated from his mother – Olsson’s mother, Yvonne – at Cairns railway station in the summer of 1950. The book opens here, at this crucial moment. Yvonne is nineteen; she is fleeing her husband and Peter’s father, Michael, a man who is “darkly beautiful” yet dangerous: violent, neglectful, a gambler.

[she is a] girl with fugitive eyes and an infant on her hip. She is thin, gaunt even, but still it is easy to see these two are a pair, dark-haired and dark-eyed. She hurries down the platform towards the second-class cars, slowed down by the weight of her son and her cardboard suitcase. It holds everything they own, everything she dared to take.

Yvonne finds a seat in one of the last cars and attempts to settle her son with some food. Moments later, a man – Michael – appears at the door, walks towards her, and roughly pulls Peter away. Yvonne stays on the train, and returns to her family in Brisbane, where she will soon give birth to Sharon, Peter’s half-sister. Within a few years, she starts a new life with a new man, Arne Olsson, a kind and gentle Swede – Kristina’s father. In the meantime, two-year-old Peter moves with his father to Junee, in south-west New South Wales, where he contracts polio. His wasted left leg is fitted with a calliper. After two years in rehabilitation at the Far West Children’s Home, he returns to his father, now living in Dungog. They will move often, and Peter becomes a serial runaway, living life on the margins of society. Mother and son will not see each other again for almost forty years – and until that moment her other children remain unaware of his existence.

Olsson gives equal weight to Peter’s and Yvonne’ stories, deftly interlacing the two narratives in short, untitled sections, many of them barely a page long, slowly building momentum towards the reunion of mother and son. In parts, the story is harrowing. Physical violence, injury, illness and pain are revealed in sensory detail: “hips and elbows and knees smack against wood”. Or they are chillingly implied: Michael “expresses his relief and concern with a variety of implements: a strap, a piece of wet rope, a dog chain.” My reaction to these descriptions was visceral – there were moments where I found myself gasping. Boy, Lost is the best kind of page-turner; its combination of a tightly-wrought structure, a predominantly present-tense narrative, and spare yet emotive prose, creates a perfectly-weighted balance between the desire to know what happens next, and to linger over the words on the page.

The loss is experienced on both sides, and Olsson is an empathic, yet impartial narrator, never making judgements, only seeking to understand why. “The only safe way in was as a journalist,” she reveals in the book’s Afterword, “objective, writing in the third person.” Peter’s story in particular is shocking, and Olsson is both compassionate and restrained in her approach, allowing certain things to remain unsaid, and the narrative to stay unresolved. The reunion between mother and son, and meeting of long-lost siblings, is a happy occasion, and after all that has come before it, the scenes that unfold in its wake provide a welcome catharsis. It must have been tempting to leave things there – to give the story a happy ending. Instead, Olsson acknowledges the temptation, and presses on.

In the weeks that followed we told ourselves a story, a fiction about a boy lost and found, a family reunited, a mother’s grief dissolved. It was simple: Peter was back; we’d get on with the business of including him in our lives. There in front of us was the happy ending we’d always strived for, unknowingly, for our mother.

But wasn’t simple and it wasn’t a story. It wasn’t entirely happy and it wasn’t even an ending. Peter embodied the fracture at the centre of our lives, and though we didn’t yet know why, I think we suspected it. . . .

In the Afterword, Olsson writes of the story’s inception: how Peter came to her four years after their mother’s death, and read to her from official documents relating to his life – court transcripts, medical records – and asked her to write his story.

So his question sounded simple, at first – in many ways it was. Peter needed to make sense of it all, I thought, to make a recognisable shape for his life. His childhood was the stuff of myth, wild and insubstantial, hard to believe. He needed to make it all real – to pin it down by speaking it and seeing it written, by making it a story. One, perhaps, that he could believe too.

Peter’s version of the story began when he contracted polio: “he was the solitary protagonist … he was the self-made hero of his life, enduring his suffering, vanquishing his foes … born with the calliper and the pain, already two years old.” As Olsson pointed out to him, that was only part of it: the boy had been stolen from his mother, that’s where the story began. In an interview with Jo Case, published by The Wheeler Centre, Olsson spoke of how it took some time before she felt she was “entitled” to tell the story. “There were so many things we weren’t supposed to know,” she said. “But entering the story with a whole heart meant I was finally able to look at my mother as the woman she was, and at my own experience.”

By exploring both sides of the story – what it means to be lost, and what it means to lose – and how this one event impacted on the wider family, Olsson has written a book that at the heart of it, seems to say: we may all be episodes in other people’s narratives, but we are also more than that. We each have our own life to lead, our own story to tell, and this life, this story, entwines with others’. In the book’s closing pages Olsson relays a phone conversation she had with Peter after she’d finished writing it. She admitted to him, in tears: “It wasn’t fair … we had her, the best of her, and you missed out.” Peter agreed, before graciously conceding that they were all lucky, that this is what Yvonne had taught them: “to see the glass half-full”. Boy, Lost is a beautifully realised testament to this legacy.

First published in The Australian Women’s Book Review in July 2014

Boy, Lost

Kristina Olsson

St Lucia: University of Queensland Press, 2013.

Works cited

Steedman, Carolyn. Landscape for a Good Woman: A Story of Two Lives. London: Virago, 1986. Print.

Olsson, Kristina. Interview by Jo Case. The Shadow of Lost Children: An Interview with Kristina Olsson. The Wheeler Centre. 16 April 2013. http://wheelercentre.com/dailies/post/4b62676bff1f/