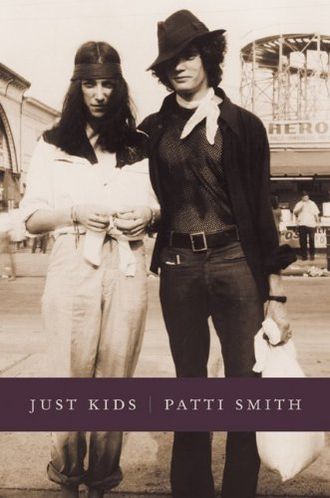

Part elegy, part bildungsroman, Patti Smith’s Just Kids, winner of the National Book Award for Non-Fiction in 2010, recounts the formative years in the lives of Patti and Robert Mapplethorpe, lovers and friends, muses and makers.

In 1966, while studying teaching at a State College in New Jersey, nineteen-year-old Patti Smith fell pregnant after sleeping with a boy “even more callow than I was”. She gave the baby up for adoption, quit college and began working in a local factory. She found solace in Rimbaud’s Illuminations, which she had stolen from a bus stand when she was sixteen, because she couldn’t afford the 99c cover price. “He became my archangel, delivering me from the mundane horrors of factory life.” When she was laid off from her factory job a few months later, she took it as a sign. She planned to track down some high school friends who were attending an art school in Brooklyn. Her friends had moved and instead she meets Robert Mapplethorpe, for the first time. She didn’t yet know his name.

Robert pointed her in the direction of her friends’ new abode, but they had moved. She slept rough for a while. It was summer, 1967; there were plenty of others doing the same. “I can’t say I fit in, but I felt safe.” She started work in a bookstore. One day Robert walked in. He bought a necklace. She said to him, “Don’t give it to anyone but me.” One night shortly afterwards, in Tomkins Park, Robert appeared just as Patti was trying to fend off the unwanted advances of an older man. Robert pretended to be her boyfriend. They spent the rest of the night wandering the East Village, then moved in together. He gave her the necklace. And so began a lifelong friendship.

There is something mythical about this meeting; it seems fated, serendipitous, the kind of meeting that only happens in movies. But Just Kids follows its own boy-meets-girl trajectory. Girl meets boy, girl and boy fall in love, girl and boy live in the Chelsea Hotel together, they make art, boy discovers he likes boys, boy and girl stay friends, boy becomes Robert Mapplethorpe – a famous photographer known for his visceral images of sado-masochism – and girl becomes Patti Smith – rock-poet and ‘godmother of punk’.

Whether this meeting was scripted by Patti herself, or by the universe, I couldn’t say; I’m not cynical enough to completely doubt its veracity, nor am I gullible enough to swallow it whole. I do know that memory is such that we reconfigure things in our minds all the time: the stories we tell ourselves make up the narratives of our lives. As Kate Holden wrote, in her piece ‘After the Words’, in The Griffith Review, “Memoir elides, it skips over tedious things, like meals and haircuts, and in its forensic focus it has no time for what won’t fit its determined narrative.”

Just Kids isn’t just a memoir. It is as much, if not more, a tribute to Robert Mapplethorpe, who died from AIDS in 1989, aged 42. In many ways, it’s Robert who we see most clearly – a young Robert through Patti’s eyes. The spotlight is on him throughout the book. She tells us of his fears, “he worried incessantly, about how we would survive, about money,” and his motivations, “Robert had a fascination with human behaviour, and in what drove seemingly normal people to create mayhem”. Equally, the Patti we see most clearly is from Robert’s perspective, through his words, and of course his photographs, which are scattered throughout the book so that Just Kids – like so much of their work – feels like a collaborative effort. In a recent interview, Smith described what was probably their greatest joint effort – the photograph on the cover of her first album Horses – as “A little bit of Baudelaire, a little bit of Catholic boy, a little bit of Frank Sinatra, and a lot of Robert.”

Not long after they met, Patti and Robert went to Washington Square, where they shared coffee from a thermos “watching the stream of tourists, stoners, and folk singers.” An older couple stopped and looked at them. The woman suggested to her husband that he take their picture saying, “I think they’re artists.” The husband shrugs and said, “They’re just kids.” And there is an innocence to the telling of this story that belies its subject matter – two young artists making their way in New York City, scratching out a living, often going hungry, at times homeless, near-destitute – and at times I wondered whether Smith was being disingenuous in her retelling. But perhaps they were more innocent times – or maybe it’s just that Patti, the hard-working Jersey girl from a tight-nit family who largely eschewed drugs, maintained a wide-eyed wonder, and at the same time a certain distance, from the seediness that often surrounded her.

Robert lived life on the edge: whether it was tripping on acid, engaging in sado-masochism, or hustling for extra cash. They were both committed to making art. In a 1995 interview in The Village Voice, Patti said of Robert, “I knew Robert since he was 20 years old, and he was driven from an early age; he had a definite calling. He wasn’t a hustler who did art, he was an artist.” Patti writes of having received a book from her mother on her 16th birthday, The fabulous life of Diego Rivera. She next summer she works in a factory, but dreams of a life beyond. “I imagined myself as Frida to Diego, both muse and maker. I dreamed of meeting an artist to love and support and work with side by side.”

This central motivation is muted in Just Kids but is evident elsewhere. In a 1973 interview in Andy Warhol’s Interview Patti said, “I’ve always been hero-oriented. I started doing art not because I had creative instincts but because I fell in love with artists…art in the beginning for me was never a vehicle for self-expression, it was a way to ally myself with heroes, ‘cause I couldn’t make contact with God.” But this was not just passive idolatry. The following year she told Rob Baker, “I started makin’ my move when all the rock stars died. Jimi and Janis and Jim Morrison … I just felt total loss. And then I realized it was time for me.”

It was time for her. Patti’s first album Horses came out in 1975, and she released three more albums before the decade was out. And while she only had one real hit ‘Because the Night’, co-written with Bruce Springsteen, she’s been cited as an influence by artists as diverse as Michael Stipe of REM and Morrissey. Towards the end of Just Kids a snippet of conversation is recalled – “Patti,” Robert drawled, “you got famous before me.”

In 1979 – just like her hero Rimbaud who gave up writing at the age of 21 – Patti gave up performing at the height of her fame, and moved to the suburbs of Detroit to raise a family. In essence this is where the story ends. The telling of Robert’s premature death from AIDS in 1989, undoubtedly the driving force behind the book, acts as a coda and is dealt with – as one would expect from a rock star who is foremost a poet – lyrically, and yet without sentimentality.

Six years after Robert died, in the space of a year, Smith lost her husband Fred ‘Sonic’ Smith, her younger brother Todd, and Richard Stohl, the keyboard player from the Patti Smith Group. And once again, she started making her move, recording new music and returning to the stage for the first time in fifteen years, proving that she had become what she had set out to be – both muse and maker.

Patti Smith’s latest memoir M Train is has just been released.

An abridged version of this review was first published at Stilts