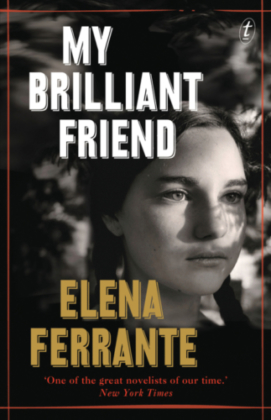

In early 2016 I went to Bali for a friend’s 40th birthday. I was to meet a group of friends from all over the world for a week of sun, sea, seafood and Bintang. I went over early, renting an Airbnb villa on the outskirts of Ubud for a few days – some downtime before meeting up with the crew. Some downtime in which to immerse myself in the world of Elena Ferrante.

Having already devoured My Brilliant Friend, the first of Elena Ferrante’s four Neapolitan Novels, I began reading the next book, The Story of a New Name, on the plane to Denpasar. That night I read until late, while outside in the garden, frogs barked. For a few hours I could hear the tinkle of gamelan and the pop of fireworks in the distance; the sounds of celebration. By midnight the party had ended; scooters stuttered on until dawn and then stopped. It was Nyepi, Balinese New Year, traditionally a day of silence and meditation. Everything was closed and everyone – including tourists – had to stay at home. I bunkered down in my villa and read and read and read.

In the four years leading up to this holiday, I had been reading memoir and creative non-fiction almost exclusively, with the explicit intent of teaching myself how to write non-fiction. I read novels rarely, and always with the expectation of experiencing, for a time, that all-encompassing joy of living in a world of another’s making. If I caught myself analysing or picking holes, I stopped. If the language distracted from, rather than fed, the central narrative, I stopped. If I felt manipulated by the plot and pacing, I stopped.

Reading Ferrante, I did not want to stop. I was not distracted. I did not feel manipulated. I was in thrall to her storytelling powers, as so many readers, and writers and critics have been. “I read these books in a state of immersion,” wrote Jhumpa Lahiri. “I am propelled by a ravenous will to keep going,” wrote Molly Fischer in The New Yorker.

In my memory the bliss of reading, of being immersed in the story of Lenú and Lila, is so tightly threaded through all the other experiences of that holiday – the seafood dinners on the sand, the massages, the marathon afternoons in the pool with friends, talking nonsense while we drank Bintang – I cannot prise them apart. Nor would I want to.

There is a part of me that doesn’t want to understand what it is about these books that makes them special.

There is a part of me that doesn’t want to understand what it is about these books that makes them special. But I have been reading as a writer for so long now that even as Naples’ violence pulsed through my veins and Ischia’s sun burned hot on my skin – as I, too, fell in and out of love with Nino – I was taking notes, filing them away. Always, at the back of my mind, I was wondering: what could Elena Ferrante teach me?

For a start, she showed me that “show don’t tell” isn’t the be all and end all of writing good fiction.

“Show don’t tell” can be handy advice for a beginner writer who reports rather than reveals, who races past important plot points, or recounts backstory instead of describing how characters interact, or what they look like, or how they fare under pressure.

It can be a useful suggestion for any writer at any stage who, in their rush to get to the end of a draft, may have privileged plot over character development, or glossed over those parts of the story that really matter: those that speak to the central themes or are key to the overall narrative arc.

The problem with “show don’t tell” is that word “don’t” in the middle.

However, show too much and your story will be static, like a beautiful painting – not a story at all. Sunil Badami wrote about this problem in a blog post for Southerly, saying: ‘Too often, misreading the idea of “show, don’t tell”, writers show us everything in the room but tell us nothing about what’s happening in their characters’ hearts. Much less anything at all: stuck looking around the room, nothing else much happens.’

The problem with “show, don’t tell” is that word “don’t” in the middle. It pits “showing” and “telling” against each other as separate and opposite, when in fact they are – or can be, as they are in Ferrante’s Neapolitan Novels – integrated to the point where they are near-impossible to parse.

In a 2015 email interview with Jennifer Levasseur for The Sydney Morning Herald (SMH), Ferrante wrote: ‘Whatever story, whatever genre it belongs to, it must develop techniques that make it appear credible not only to those who read, but also to those who write.’ I am intrigued by the idea that a story develops its own techniques, and by the inference: that these techniques might then differ from story to story.

Throughout the Neapolitan Novels, scenes are not set in the traditional sense, or set apart, even, from the surrounding tumult of Lenú’s narration. Her drive to understand her friendship with Lila, her ambition, her obsession with Nino, her relationship with Naples and the neighbourhood, is ever-present. Even as she is remembering and attempting to describe events as they happened, she is reflecting and interpreting her feelings and thoughts, and her own and others’ behaviour.

There is no ebb and flow, no shifts in gear.

Because of this, Lenú tells as much as – and perhaps more than – she shows. The day after losing her virginity to Donato Sarratore, Lenú remembers: ‘[I] woke up cheerful’ and ‘even when Nino, Lila, and what had happened at the Maronti came back to me, in fragments, I still felt good.’ She interprets rather than describes others’ thoughts and feelings, especially Lila’s: ‘She discovered that wealth no longer seemed a prize and a compensation, it no longer spoke to her … The relationship between money and the possession of things had disappointed her.’ All of this unfurls with the same sense of urgency. There is no ebb and flow, no shifts in gear.

In the same interview with the SMH, Elena Ferrante wrote that Lenú’s ‘compulsion to narrate is a fundamental part of the story, almost its summation: she wants to pin Lila down once and for all, she wants to be tied to her definitively.’ It is this compulsion – Lenú’s urgent and pressing need to know and understand her lifelong friendship with Lila – which brings an absolute and undeniable credibility to the Neapolitan Novels’ narration and invokes in us a “willing suspension of disbelief”. And so Ferrante shows us, through Lenú’s narration, what the story is about.

‘I’m a storyteller,’ Ferrante wrote, in a 2014 Q & A with The New York Times. ‘I’ve always been more interested in storytelling than in writing.’ Fortunately for us, as readers and as writers, she is a master of both.

A version of this essay was first published in September 2016 by Writing Queensland, the online magazine of the Queensland Writers Centre.